- arabchanter

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 12/3/2015

- Posts: 2,393

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

Album 496.

ABC...................................the Lexicon of Love (1982)

Martin Fry's ABC were arty punk funksters from the same Sheffield scene that spawned Caberet Voltaire and The Human League. Buggles frontman Trevor Horn produced them,which could have been a disaster but instead became a match made in pop heaven.

Horn and Fry programed the arrangements for each song using a primitive sequencer,a Mini-Moog and a drum machine. Then the band re-recorded every part, erasing the synth demos as they went along,"it was like tracing" says Horn,"Which meant we got it really snappy and in your face"

The grandiose settings are constantly undercut by Fry's beautifully bleak lyrics about the impossibility of love and the illusory nature of beauty.

I had this one back in the day.

I don't know a lot, but I know what I like!

- PatReilly

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 25/3/2015

- Posts: 5,580

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

arabchanter wrote:

Yeah, sorry about the break in service there, but a bit of bad news last week.

I don't know how many people seen it on the news or in the paper,but my street was cordoned off for a bit last week,we had the boys wi' the hazmat suits on and athing, done a' their tests then hit me wi' the results, and it was as I feared.............Man Flu!

I'd only gone and contracted the dreaded curse of the male of the species, so that was me stuck indoors in my scratcher, hoose sealed aff, and mrs chanter told in no uncertain terms to "make sure my life insurance was up to date" and to try and "make me as comfortable as can be expected in the given circumstances"

In the last week e've been tae Hell and back, now it was touch and go for a while, and to be honest "eh wisnae worth a penny" fir most of it, but wi' the help of loved ones and the generous Red Cross parcels launched over the fence wi' all sorts of extendable pole type o' gadgets from the neighbours, I can proudly say................I'm a survivor!

Got the all clear fae the hazmat boys on Monday, so back in the game the day.

Close shave there! Glad to see you've survived, many don't.

- arabchanter

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 12/3/2015

- Posts: 2,393

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

shedboy wrote:

arabchanter wrote:

shedboy wrote:

Maybe take out my pissed contributions mind you ;)

If you take out the pissed contributions and meanderings, you might have enough left for a flyer!

not sure its a compliment lol as ive spouted some shite ;)

You and me both ![]()

I don't know a lot, but I know what I like!

- •

- arabchanter

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 12/3/2015

- Posts: 2,393

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

Album 497.

Prince..............................................1999 (1982)

1999 was Prince’s breakthrough release that cemented his status as a star and paved the way for his next release, the even more successful Purple Rain. 1999 is, however, tremendous in its own right. The 2xLP, the first of many produced by Prince, mixes conservative rock, experimental synthpop, and his expected Minneapolis funk into a record of monumental proportions. Double-Vinyl releases were still uncommon and some countries sold them as separate vinyls – 1999 I and 1999 II.

The chaotic-yet-controlled title track opens the album and served as its first single, but was the last of its songs to be recorded, which Prince only made when prompted by Warner Bros. Records for a “summarizing track” (Purple Rain would come about following a similar request in 1984.) After the album’s release on October 27, 1982, there wasn’t another single until the pop-rock hook up song “Little Red Corvette” in February 1983, becoming his first Top 10 single since 1979’s " I Wanna Be Your Lover". Its success caused “1999”’s reemergence and both singles took over radio, their videos falling into deep rotation on MTV – the first for an African-American artist – and both became rock standards.

The CD and Cassette edition, limited in their capacity at the time of the release, had to omit the 8-minute “D.S.M.R.”, which saw a release as a promo single to radio in Spring 1983 – the prideful, yet sad “Free”, replaced it on cassettes at the end of Side 1 instead of its normal place at the end of Side 3 (Disc II, Side I). Certain 1-LP Vinyl Issues also omitted the 9 ½ minute sexually synthesized “Automatic”, release as a single in Australia. Baby-cooing, jukebox blues-like “Delirious” served as the third full single on August 17, 1983 and the second to crack the Top 10. “Let’s Pretend We’re Married”, a worthy addition to Prince’s array of erotic tunes, was the fourth fully-released single, sixth overall, and last from 1999, in November 1983. Album-only track “Something In the Water (Does Not Compute)” serves as a similarly-themed prequel to "Computer Blue", both robotic-like songs about failings in the search of love; “Lady Cab Driver” is a funk-pop composition describing an encounter between a cabbie and her passenger; The song “All The Critics Love U In New York” serves as mockery of the landscape of musical journalism; “International Lover”, a powerful classic full of Prince screeches and ad-libs, rounds out the album.

The 1999 era bore many important changes to Prince’s career. His backing band – then consisting of Dr. Fink, Lisa Coleman, Jill Jones, Bobby Z., Brownmark, Wendy Melvoin, and Dez Dickerson – were included in the creative process for the first time and while not playing any instruments on majority of the records, were alongside Prince in the music videos for the album’s singles (most of which were filmed in the rehearsal period of The 1999 Tour, his most elaborate and successful tour to date). The album and promo also featured his first extensive use of the color purple, especially in the artwork (assumed to be drawn by Prince himself) and wardrobe. The eyes in “1999” and “Rude Boy” pin are taken from the cover of Controversy, and written backwards in the football within the ‘i’ of Prince is “and the Revolution”, recognizing his band under this name for the first time. Dez Dickerson said:

“It was always part of the rhetoric. He wanted a movement instead of just a band. He wanted to create that kind of mind-set among the fans.”

Double album, gonna be a weekend listen.

I don't know a lot, but I know what I like!

- •

- Finn Seemann

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Online!

Online!

- Registered: 24/5/2018

- Posts: 1,899

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

arabchanter wrote:

Album 496.

ABC...................................the Lexicon of Love (1982)

Martin Fry's ABC were arty punk funksters from the same Sheffield scene that spawned Caberet Voltaire and The Human League. Buggles frontman Trevor Horn produced them,which could have been a disaster but instead became a match made in pop heaven.

Horn and Fry programed the arrangements for each song using a primitive sequencer,a Mini-Moog and a drum machine. Then the band re-recorded every part, erasing the synth demos as they went along,"it was like tracing" says Horn,"Which meant we got it really snappy and in your face"

The grandiose settings are constantly undercut by Fry's beautifully bleak lyrics about the impossibility of love and the illusory nature of beauty.

I had this one back in the day.

Classic album - pity the first album was the peak of their powers.

- arabchanter

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 12/3/2015

- Posts: 2,393

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

Album 495.

Abba.............................The Visitors (1981)

This was a strange Abba album, none of yer "dance roond yer handbag" numbers on this one,more sad/bitter "I've been fucked over" kinda tracks.

This album made me think it would be better as a morbid/bleak West End musical, as all of the tracks seemed over-orchestrated and miserable for this listener, and not something I would want to play at all.

As no tracks done anything for me, this album wont be going into my collection.

Bits & Bobs;

Have written about Abba previously in post #1348 (if Interested)

The Making of The Visitors

On November 30, 1981, ABBA’s final studio LP, The Visitors, was released in Sweden. The album was the sound of a group coming to terms with their marital splits and the prospect of life after ABBA. In this feature we take a look at the making of the group’s most controversial piece of work.

Exploring Their Private Lives

On March 16, 1981, Björn, Benny and their four trusted backing musicians – Lasse Wellander, guitar, Rutger Gunnarsson, bass, Ola Brunkert, drums and Åke Sundqvist, percussion -– entered Polar Music Studios together with engineer Michael B. Tretow to start work on the first batch of backing tracks for ABBA’s eighth studio album. Only five months had elapsed since they completed work on their previous LP, Super Trouper, but ABBA was no longer the same group. Just four weeks before these initial recording sessions, Benny and Frida had announced their decision to go their separate ways, just like Agnetha and Björn had done in 1979. Thus, the group that had once consisted of two couples was now made up of four colleagues, sharing a sense of respect for the professional capacities of each member, but not socialising very much outside the recording studio.

Although ABBA often wanted to avoid making their private feelings public in their music, at least in an overtly literal way, the past few years had seen a change in attitude in that respect. Two of the songs recorded during the initial sessions for the new album were certainly coloured by recent events within the group. ’When All Is Said And Done’ dealt expressly with the split between Benny and Frida, exploring the inevitability of their separation. Frida handled the lead vocals, and Björn, who wrote the lyrics, made sure that she felt okay with the subject matter. Frida assured him that she was only eager to get this chance to express her true feelings. ”All my sadness was captured in that song,” she later recalled.

But Björn didn’t stop at exploring the feelings of his fellow band members at this time, he also did some private soul-searching. The lyrics for ’Slipping Through My Fingers’, also recorded during the first sessions for the new album, pondered the conflicting feelings of parenthood. The direct inspiration was seeing his seven-year-old daughter Linda walk off to school one day. ”I thought, ’Now she has taken that step, she’s going away – what have I missed out on through all these years?’” No doubt, his feelings acquired another level of depth, considering the fact that Linda and her younger brother Christian no longer were living under one roof with both their parents. The lead vocalist on the song was, of course, Linda’s mother, Agnetha.

Shades Of Darkness

Kicking off the sessions with feelings of sorrow and regret certainly put its mark on much of the album. There were exceptions: the bizarre story of a man answering an ad in the personal column, placed by a girl and her mother, as depicted in ’Two For The Price Of One’, performed by Björn himself, was one. The other was ’Head Over Heels’, the story of a high-society lady dragging her exhausted husband to parties and in and out of boutiques, sung by Agnetha. Although it was eventually issued as a single, it was one of ABBA’s least successful seven-inch releases since their breakthrough, perhaps proving that the group were now only truly convincing when they explored darker territories.

The album sleeve was photographed at the studio of artist Julius Kronberg. The first single off the album was the Agnetha-led ’One Of Us’ – ABBA’s final major worldwide hit – which dealt with a woman wishing that she could patch up a dead relationship, a divorce story that paralleled ’When All Is Said And Done’. Elsewhere on the album, darker subjects such as cold-war era threats of world destruction were explored in Agnetha’s ’Soldiers’, while the Frida-sung title track, ’The Visitors’, dealt with the fate of dissidents in the Soviet Union of the time. The closing selection, ’Like An Angel Passing Through My Room’, was a woman’s solitary musings, featuring only Frida’s voice accompanied by a very bare synthesizer arrangement. Bleak, indeed.

Believing In Angels

Sessions concluded with a mixing session for ’Soldiers’ on November 14, but by then the concept for the album had already been created. As usual, ABBA’s trusted sleeve designer, Rune Söderqvist, was the man behind the artwork. After giving the matter some thought, Rune came up with an ”angel” concept. The ”visitors” of the album title might very well be angels, he thought, and besides, the album included a track entitled ’Like An Angel Passing Through My Room’. The next step was to develop that concept into an idea for the album cover. ”I knew that the painter Julius Kronberg had painted a lot of angels in his time,” Rune recalled, ”so I located his studio – at the Skansen park [in Stockholm] – which contained several of his paintings.”

Together with photographer Lasse Larsson – who also shot the Super Trouper album cover –Rune Söderqvist assembled the group in the cold, unheated studio, and arranged a picture of them with a giant painting of an angel as backdrop. For the first time on an album cover, the members were depicted as separate individuals rather than a close-knit group. The physically chilly environment and the general sense of fatigue at being ABBA no doubt contributed to the mood at the photo session. ”We might not go on working with this forever,” Björn remarked at the time. ”We’ve emptied ourselves of everything we’ve got to give.” Indeed, the following year the group released only two further singles of newly recorded music before going their separate ways.

For Björn and Benny it was no longer creatively challenging to go on working within the ABBA concept. One track on The Visitors underlined their ambitions for the future: ’I Let The Music Speak’, with vocals by Frida, was structured very much like a theatrical number. Björn and Benny had long been thinking about writing a full-length musical, and during 1981 those thoughts were closer to being realised than ever before. The Visitors was released on November 30, 1981 and just two weeks later, Andersson and Ulvaeus had a meeting in Stockholm with lyricist Tim Rice – famous for his work with Andrew Lloyd Webber – discussing a potential collaboration. These initial talks eventually resulted in the musical Chess. ”If ABBA hadn’t recorded ’I Let The Music Speak’, I guess we would have used it in Chess,” Björn reflected later.

Today, many people seem to remember ABBA mostly for happy, uptempo songs like ’Waterloo’, ’Dancing Queen’ or ’Take A Chance On Me’, connecting it all with colorful 1970s fashion and hairstyles. But anyone who takes a listen to The Visitors – or, indeed, previous hits like ’SOS’, ’Knowing Me, Knowing You’ and ’The Winner Takes It All’ – will find that beyond the superficial image, there are darker shades to much of ABBA’s output. Frida probably summed it up best when she reflected on The Visitors: ”When you’ve gone through a separation, like all of us had done at the time, it puts a certain mood on the work. Something disappeared that was so fundamental for the joy in our songs, that had always been there before. … Perhaps there was a bit of sadness or bitterness that coloured the making of that album.”

I don't know a lot, but I know what I like!

- •

- arabchanter

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 12/3/2015

- Posts: 2,393

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

Album 496.

ABC...................................the Lexicon of Love (1982)

Well, I fair enjoyed re-visiting this album.What's so good about this album then, well for starters you've got Fry's very articulate songwriting, then you add in the not insignificant genius that is Trevor Horn,working his magic on the production.arrangement side of things,not forgetting his team (who went on to form The Art of Noise)

This album is smooth,sophisticated and a great listen, even if you took off the four singles "Poison Arrow," "Tears Are Not Enough,"The Look Of Love " and my personal favourite "All Of My Heart" I think I would probably still buy it as the other tracks are not a kick in the arse behind the afore mentioned songs.

Martin Fry oozed cool and sophistication,also had a very distinctive yet underrated vocal style that I thoroughly enjoyed, but in saying that, I wouldnay want to stuck in the trenches wi' him, I reckon he'd throw a tantrum if he ended up with "helmet hair"

Anyways, whether it's nostalgia (although I did find it as fresh as I remembered it) the cracking lyrics (do yourself a favour and read the lyrics while listening) or the warm and faultless production of Mr Horn, this album made me feel damn good.

This album will be going into my collection.

Bits & Bobs;

How we made: ABC's Martin Fry and Anne Dudley on The Lexicon of Love

'There was a touch of James Bond to it all. It was all very aspirational and cosmopolitan'

Martin Fry, singer-songwriter

Disco was a dirty word by 1982. But I loved the strings on Chic records, and the whole soundscape of Earth, Wind & Fire. Fusing that with the likes of the Cure and Joy Division was what we were after – while Mark White, our guitarist, was keen to give the album the feel of a film soundtrack. The highly theatrical sleeve even had a touch of that old movie classic The Red Shoes to it: that was a pretty bonkers film, more intense and emotional than factual. The Lexicon of Love is a bit like that. I used a lot of falsetto, partly to convey the rollercoaster ride – the elation and despair – of being in love.

We'd made the top 20 with our first single, Tears Are Not Enough, in 1981, and wanted this follow-up album to be more polished. After hearing Dollar's Hand Held i Black and White, which had this panoramic, widescreen sound, we approached its producer, Trevor Horn. He got what we were trying to do immediately. We were full of ideas and thought we could change rock'n'roll – very ambitious for guys who'd just been signing on the dole in Sheffield.

Lyrically, while I loved the likes of Gary Numan and OMD, I wanted to take my songs to a more emotional level, along the lines of Rodgers and Hammerstein or Cole Porter. At that time, there were few songs about really loving or hating someone; and, whereas punk had been quite blokey, women make their presence felt in Lexicon. It was unusual to feature strings so prominently, too, unless you were Cilla Black or Cliff Richard. The Look of Love, which got to No 4, had all these pizzicato arrangements over a moog bassline, while All of My Heart (No 5) was very Bridge Over Troubled Water.

Imagewise, the gold lame suits and dinner jackets were us turning away from punk. There was an element of James Bond to it all, very aspirational and cosmopolitan. Thirty years on, I'm performing these songs with a full orchestra. I've lived a full life and have two children now, so it's interesting coming back to All of My Heart – and singing it as a man rather than a boy.

Anne Dudley, keyboards, arranger

ABC had no keyboard player, so Trevor Horn brought me in. At some stage during the recording of The Look of Love, he decided it needed a real string and brass section. With the confidence of youth, I volunteered to do the arrangement, even though my experience was minimal. When we recorded the 30-piece string section at Abbey Road, I was often the youngest person in the room. I'd always loved the orchestral flourishes in Gamble and Huff's disco classic The Sound of Philadelphia. These became my chief inspiration, alongside the soaring yet simple string lines in Bee Gees records; and there was even a bit of Vaughan Williams in there, too.

I remember hearing the mix of The Look of Love and being amazed at how loud Trevor had made the strings. It was really nailing the ABC colours to the mast: this was to be an unapologetically lush and epic album. From then on, it was a given that we would add strings to many tracks, developing the unique sound of the album – a combination of cutting-edge technology, electronic sounds and real instruments. It's a mixture I've been exploring ever since.

To be honest, I thought All of My Heart was rather weak at first, until Trevor added the dramatic pause at the end of the chorus, before the line "all of my heart". We then mixed in some timpani, while the fadeout was a chance for me to have an English pastoral moment. In the end, it was probably Martin's best vocal performance, and it became a stand-out song. But the tracks were all outstanding, Martin's witty and effortless lyrics encapsulating the trials of young love. The Lexicon of Love made it to No 1, and I'm delighted with how it sounds 30 years on – and not too embarrassed by my youthful efforts.

"Tears Are Not Enough"

ABC's first single was a spare funk tune produced by Steve Brown in which Martin Fry contends that "tears are not enough" to prove that a girl's emotions are genuine. The song peaked at #19 on the UK singles chart, whilst in the US, it was released as the B-side of "Poison Arrow."

The version that can be heard on the Lexicon of Love album was re-recorded by the band and produced by Trevor Horn. It features lavish orchestration by Art Of Noise's Anne Dudley, one of several on the LP. According to Horn, they were her first ever string arrangements.

"The Look Of Love"

You need to read beyond the title on this one - it's not a chirpy love song, but about how to deal with it when love goes away. ABC lead singer Martin Fry told Uncut that this song is "genuinely about the moment you get your teeth kicked in by somebody you love f--king off. You feel like s--t but you have to search for some sort of meaning in your life."

A track from the group's first album, this was ABC's biggest hit in the UK, peaking at #4. It also topped the Canadian singles chart.

On the album, this song is listed as "The Look Of Love (Part One)," with the last track being a short version of the song called "The Look Of Love (Part Four)." What happened to parts two and three? They appear on the 12" single along with the others. Part Two is an instrumental, and Part Three is a remix.

Martin Fry mentions his forename in the lyric when he sings: "They say 'Martin, maybe, one day you'll find true love.'"

Trevor Horn, who was also involved with Yes, The Buggles and The Art Of Noise, produced this track. He also did a remix, "The Look of Love (Part 5)," using a Fairlight synthesizer. This 12-inch single, whic was issued to club DJs, may have been the first instance of a pop song being remixed with scratching and it was among the earliest remixes to be based upon samples.

MTV played a big role in ABC's American success, and the video for this song was a favorite on the network, which launched in 1981. The clip was directed by Brian Grant, and inspired by old Hollywood movies. Martin Fry describes it as a cross between An American In Paris and The Benny Hill Show. Grant's videos were all over MTV in those early years; his other work includes "Stand Back" by Stevie Nicks and "Saved By Zero" by The Fixx.

The band's appreciation of Smokey Robinson is well documented, and Smokey had "the look of love" long before ABC. In his 1971 song "I Don't Blame You At All" (a #11 hit in the UK), he sings, "What I thought was the look of love was only hurt in disguise."

Thought I'd share this interview with Trevor Horn, I found it rather interesting;

2 February 2012 Interview: Trevor Horn

‘That coldness; that precision’: Simon Price meets the man who invented the eighties There’s a moment in ‘The Troggs Tapes’, the sixties band’s legendary studio outtake, in which drummer Ronnie Bond, during a heated debate over the sound of their new single, argues, in a richly agricultural accent, “You’ve got to put a little bit of fucking fairy dust over the baaastard.”

If any man on earth knows all about putting a little bit of fucking fairy dust over the bastard, it’s Trevor Horn. If you hear any record from that golden period between punk and Live Aid which shimmers and sparkles and seems to fly above the earth, it was either produced by Trevor Horn (see: The Buggles, ABC, Frankie Goes To Hollywood, Grace Jones, Dollar, Pet Shop Boys, Propaganda, Malcolm McLaren and countless others), or trying to sound as if it was (see: pretty much everyone else). The immaculate cleanliness of what Paul Morley christened ‘the new pop’ was Horn’s handiwork. He is, essentially, the man who invented the eighties.

Lenses as thick as milk bottle bottoms, he relaxes on a brown leather sofa in the loft of his own Sarm Studios, the converted Notting Hill church whose history dates back to legendary seventies sessions by Led Zeppelin and Bob Marley And The Wailers. It’s very much a working studio: intermittently, the conversation is disrupted by thunderous bass explosions from the floors below, and he explains “Sorry, that’s The Prodigy recording their new album.”

The pretext for talking to Horn is his involvement in 30/30, a collaborative project between the EMI label and the Roundhouse venue which offers unsigned artists the chance to work with top producers for free (Trevor’s recorded a track with 22-year-old Londoner Azekel), but at any given time, Horn has several plates spinning. He’s just announced, for example, that his old band The Buggles will go on tour for the first time ever in 2012.

“I’m keen to get out on the road and play live,” he says, smiling and habitually squeaking his shoes together as he speaks. “I’ve been stuck in a studio for 30 years. The Buggles never played live at the time! That was the joke. When that thing [he means ‘Video Killed The Radio Star’] was a hit, I’d been a bassist for years, I’d played on all kinds of things…”

Born in 1949, Horn’s early life, growing up in Durham with schoolteacher father and a mother from a mining family, could barely have been further from the swing of things.

“I didn’t come to London till I was 21, and it was a different world then: all these ballrooms like the Hammersmith Palais would have a DJ, but they would also have a band. And it was a way to earn a living as a musician. Two nights a week, the ballroom dancing would stop, then we’d play whatever was in the charts. I could read music, and I could play bass, which was a very new instrument in the early seventies, so if you could do those two things, you could make a living. And I was really stupid and I used to behave badly and get drunk and do all kinds of silly things because I was bored out of my mind.”

That boredom proved productive.

“When I got to 25 I left London, went back to the provinces and built a recording studio — me and another guy, with our bare hands. And I started fixing up other people’s songs — people who’d won a local songwriters’ competition, and someone said to me, ‘You know, what you’re doing is called being a record producer.’ I’d seen that credit on records but I never knew what it was. And I just had this moment where I knew that was what I was going to do. From that moment, it took me six years to get my first hit, and I earned my living playing crap and whatever.”

That “crap and whatever” included an album with CBS-backed flop John Howard, and his own “sci-fi disco” project Chromium, whose single ‘Caribbean Air Control’ featured an early example of Horn’s sonic inventiveness.

“This was ’77, and I made a ‘drum machine’ using tape and getting my drummer to play fours,” he says. “People would say, ‘It sounds like fuckin’ machines!’ and I’d reply, ‘That’s exactly the point!’”

Even though punk was going on around him, Horn was never a convert. “Being a muso, it wasn’t easy to be a fan of punk. Although I think I became more of a fan of punk when I was in America in 1982, and I got so angry with American radio, and then ‘Should I Stay Or Should I Go’ by The Clash came on the air and I had tears in my eyes. I thought, ‘It’s so crap, it’s fantastic!’”

Nevertheless, in a roundabout way, the punk explosion did affect Horn’s thinking. “In the seventies there were rock gods — Elton John, Rod Stewart — everyone sounded fabulous, everyone could sing really well, and it was daunting. Then the punk thing happened, and I thought, ‘If people will listen to that, what am I afraid of? I can do anything!’”

Horn wasn’t a lover of disco either, despite a stint playing bass for producer Biddu and his protégée Tina Charles, of ‘I Love To Love’ fame.

“I hated that shit,” he remembers, “but that’s what I played. I was Tina Charles’s boyfriend for a while. I learned a lot from her. Tina came home one night with the first backing track from a professional producer I’d ever heard. I’d tried making my own backing tracks but they sounded wrong. Biddu knew what he was doing: the drum machine was tight, everyone played exactly what he told them to, it was all really well put together. And I played it all night, thinking that’s what I’m trying to get to: that coldness, that precision.”

Horn’s dreams of being a renowned session man were starting to fade. “I flirted with jazz rock. I wanted to be Stanley Clarke. Tina Charles told me that if I practised for every minute left in my life I would never be as good as Stanley Clarke, and that all I was was a loser.”

However, it was while he was on Charles’s payroll that he and bandmates Geoffrey Downes (keyboards) and Bruce Woolley (guitar) conceptualised what would become Horn’s ticket to stardom: The Buggles.

The Buggles, ‘I Am A Camera’

“The idea came about because Bruce and I loved The Man-Machine by Kraftwerk, and the records Daniel Miller was making as The Normal — ‘Warm Leatherette’. We even read JG Ballard’s Crash because of that. It was an interesting time, you could feel something was coming in the eighties. We had this idea that at some future point there’d be a record label that didn’t really have any artists — just a computer in the basement and some mad Vincent Price-like figure making the records. Which I know has kinda happened, but in 1978 there were no computers in music yet, really. And one of the groups this computer would make would be The Buggles, which was obviously a corruption of The Beatles, who would just be this inconsequential bunch of people with a hit song that the computer had written. And The Buggles would never be seen.”

That hit song, ‘Video Killed The Radio Star’, took a while to materialise. “We had the opening line for ages — ‘I heard you on the wireless back in ’52’ — but couldn’t figure out the next line. Then one afternoon we were chatting and it just came — ‘lying awake intently tuning in on you’ — because we were talking about Jimmy Clitheroe and Ken Dodd and the classic age of fifties radio comedy. And I’d read The Sound-Sweep by JG Ballard, and some of that was in there — the abandoned studio, ‘rewritten by machine on new technology’… ‘Video Killed The Radio Star’ just popped out.”

Released in September 1979, the fiendishly catchy single was a number one across the world (and, famously, became the first song ever played on MTV). Suddenly, at the age of 30, Trevor Horn was a pop star.

Regarding never touring, he says: “We were eminently able to play live — we were musos and ‘Video Killed The Radio Star’ was relatively easy to play. What held us back was we went all over Europe promoting that single, then the follow-up ‘Living In The Plastic Age’, then we met Yes!”

In one of the most incongruous transfer deals of the eighties, the sugary synth-pop act were swallowed up by the monsters of prog rock, who had a vacancy for a singer and a keyboardist.

“Suddenly I was impersonating Jon Anderson in front of 24,000 people,” says Horn. “When someone offers you something like that, c’mon, you’ve got to do it…

It was a great experience. And it makes you a bit fearless in a recording studio. What else can life throw at you?”

Life in a touring stadium rock band wasn’t to Trevor’s liking, and after seven months he quit. Downes, however, stayed on board. “Geoffrey had had a taste of something other than novelty hit pop-dom, and he wanted to go and rock. And I didn’t blame him. The choice between staying in The Buggles and selling five million albums with [supergroup] Asia, as he went on to do, was an easy decision.”

ABC, ‘The Look Of Love’

Adventures In Modern Recording, the second Buggles album, was practically a Trevor Horn solo effort. Considered a cult classic by aficionados of studio-craft, it was a commercial failure. “I think the songs are terrible,” he admits, “but the production is great.” By the time of its release, however, Horn had already found his vocation: producing records for other acts.

“It was kind of unconscious,” he continues. “My wife [Jill Sinclair] owned a studio. And when Geoffrey left The Buggles, Jill became my manager. She said, ‘My first bit of advice is that as an artist, you’ll only ever be second or third division, however hard you try. But if you go into production, you’ll be the best producer in the world.’ She was quite purposeful. And the first thing she suggested was Dollar. I said, ‘Why would I wanna work with Dollar!? A cheesy pop duo.’ And she said, ‘Do a Buggles record, but have them front it.’ So I met them, and that’s exactly what they wanted.”

The saccharine duo of David Van Day and Theresa Bazar were all but washed-up till Horn took them on as his playthings and used them, on a run of singles including the sublime ‘Hand Held In Black And White’, as a vehicle to showcase his ideas.

“There was something sweet about them — these little people living in this techno-pop world — and we wrote ‘Hand Held In Black And White’ on the spot. The same afternoon we wrote ‘Mirror Mirror’, which was about them looking at each other. I thought it came out well, but I never thought much about it until I ran into Hans Zimmer [Hollywood composer and Buggles collaborator], who said, ‘I heard your record with Dollar, it’s really good,’ and loads of people seemed to like it. Then an astounding thing happened: the NME liked it! Paul Morley liked it. And then I was on a roll. It was epic. I only did four songs, and the final one, ‘Videotheque’, was about them seeing themselves on film. So it was like a little opera.”

The Dollar project led onto Horn’s masterpiece, ABC’s The Lexicon Of Love.

“My wife found ABC, again. She was looking for a bright young band, and they were smart guys. And they were hilarious. They said to me, ‘If you work with us, you’ll be the most fashionable producer in the world, because this week, on Thursday, we were the most fashionable band in the world.’ They went to this club in Sheffield, where they were at university, and they used to dance to soul records, and they wanted to make their soul record. It took me a bit of time to get what they wanted, because to me, it was disco. But it was disco a generation on.”

Horn says that “samplers were just starting to come in on that album” and indeed he and his team were pioneers of the use of sampling in pop.

“Geoffrey had one of the first Fairlights [a digital sampling synthesiser] that made it to England. We used them on the second Buggles album, and with Yes on Drama. I think we were the first people to put a human’s voice in it, on Dollar’s ‘Give Me Back My Heart’.”

Given that Horn’s aim was “coldness and precision”, the sampler was the perfect tool.

His next big project was Duck Rock with Malcolm McLaren, who had just discovered the black American craze for scratching — a technique of ad hoc ‘sampling’ which must have seemed strangely primitive next to the Fairlight.

“That’s what drew me into it!” he says. “At first, Malcolm was talking about ‘world music’. All that South African stuff that Paul Simon took up later, we were there two years earlier on ‘Double Dutch’. But Malcolm said, ‘In New York the black kids scratch European techno records.’ And I was like, ‘What? Don’t they like soul music?’ He said, ‘Nooo! They’re into Kraftwerk and Depeche Mode!’ And it was all starting to kick off. The first time I heard scratching was on ‘Buffalo Gals’, and I thought it was fucking amazing. It was the same thing as the Fairlight, really. What a great guy Malcolm was. If he grabbed onto an idea, you couldn’t stop him, even if it seemed so hopeless at times. You could listen to him talk for hours. I remember being sat on a New York street with Malcolm and [engineer] Gary Langan, going there at lunchtime, and the next time I looked at my watch it was eight o’clock in the evening.”

In 1983, Horn reunited with Yes, this time as a producer for the album 90125, featuring one of his most revered creations: ‘Owner Of A Lonely Heart’, a berserk piece of sliced-and-diced symphonic metal.

Grace Jones, Slave To The Rhythm

The Art Of Noise, the entirely electronic act Horn formed with Gary Langan, Anne Dudley, programmer JJ Jeczalik and journalist Paul Morley, grew from those Yes sessions. They were the first band on ZTT, the Futurist-inspired label Horn set up with Paul Morley. It was a strange union: the studio boffin and the arch-conceptualist.

“I didn’t realise what music journalists did,” says Horn. “Not really. Then I kind of got it with Paul. What they do is romanticise us. And there’s a need for that, because I’m not really going to romanticise myself. So I thought Paul would be an exciting guy to start a label with. And it was exciting for a while. The problem with record labels, however, is that when you start, everybody wants your input, but the minute the artists are established, they want you out of the way. And it’s ‘theirs’. If you wanna hang on in there, you need to be more pragmatic. And Paul, in 1984, was mental. He and my wife Jill would fight like hell, and I had to be in the middle of that. But out of that comes friction, fire…”

ZTT’s biggest success, by far, came after Horn spotted a quintet of pervy Scousers in leather jockstraps on television.

“I’d had a big row with Yes and I wasn’t speaking to anybody in the band. Then this group called Frankie Goes To Hollywood came on The Tube and Chris Squire [Yes bassist] said, ‘They look like the sort of band you should have on your new record label.’ I can’t remember being particularly smitten by the song, but what I did like was the drummer — the way he was playing four-on-the-floor. And then I was driving home listening to David Jensen on Radio 1, and he played a session of ‘Relax’. And the song was all about gay sex, but they were being ever-so-polite when he interviewed them. I came in and I said to my wife, ‘I think we should sign this band called Frankie Goes To Hollywood.’ I remember meeting them, and they said they wanted to sound like a cross between Kiss and Donna Summer, and I thought that was great.”

Frankie’s first single, ‘Relax’, was one of the biggest-selling singles of the decade (with the unwitting assistance of a “ban” from Radio 1’s Mike Read), and pioneered the format of the multiple 12”.

“We ‘performed’ the 7” version — the band playing their instruments, JJ on the Fairlight, me operating the drum machine, altering it as we went along. Then we did a version for 14 minutes that we called the Sex Mix that I did some pretty gross things over — just fucking around — and it didn’t have the song anywhere in it. The first 10,000 12”s that came out didn’t have the song: they just had ‘Ferry Cross The Mersey’, the Sex Mix, and a Paul Morley interview on the back. And we got LOADS of complaints, particularly from gay clubs who were angry about some of the noises on the Sex Mix.

“The record had been out for a few weeks and it wasn’t doing much. Then I was in New York with [then-Island Records boss] Chris Blackwell, and he took me clubbing to Paradise Garage, which really opened my eyes. The DJs — the New York Citi Peech Boys — were playing records including a lot of my 12”s, like the ABC ones, but they also had projectors and drum machines and synths, and it was huge. And when I saw that, I realised I needed to go and do another mix of ‘Relax’ so it would go over at a place like that — ’cos when you play it really loud, through those bins, you barely need anything else but the drum machine. So I went to the Hit Factory in New York, and the engineer there… I could tell he didn’t like it and I had to really push him, saying, ‘Look, I know this is all drum machine, but that’s what you have to do to make it work. Push that there, push this here.”

The Art Of Noise, ‘Moments In Love’

Not everyone got the Frankie thing, especially Stateside.

“I remember I was working with Foreigner when ‘Relax’ came out, and someone sent over the video — you know, the pissing one. Foreigner said, ‘You think this is GOOD!?’ And I was like, ‘Um, yes I do, actually! Although I wasn’t expecting the pissing…’”

Another eighties tour de force was Horn’s one-off collaboration with cuboid-headed, chat show host-slapping fembot Grace Jones.

“Grace was a trip. I only did one track with her, ‘Slave To The Rhythm’, but I got a bit carried away and did six different versions. When she did that song at my Prince’s Trust Concert at Wembley in 2004, it was such a moment: I saw hardened musos in the band with tears in their eyes. But when I asked her to do it, she had a right go at me about how I never return her calls, how she hated the music business, and at the end of it all I said, ‘Sorry, but will you do this show?’ She said, ‘I’ll do it, but it will cost you.’ I said, ‘Cost me what? From my pocket? From my soul? From whatever else?’ And she said, ‘ALL OF THEM!!!’”

I wonder whether Horn consciously distinguishes, in his own mind, between records where he’s simply doing a professional job and records where he’s creating art.

“It’s an interesting question,” he says. “They’re all pop records, really, and they’re either hits or they’re not. ‘There You’ll Be’ by Faith Hill is a very good record, but it’s completely different from ABC. But there was a point in the eighties where I suddenly just stopped messing around with all the sampling stuff. I’d had enough of it. There was too much of that stuff by that point anyway, and everyone was all over it.”

One of Horn’s biggest post-eighties successes, Seal’s ‘Kiss From A Rose’ (for which he won a Grammy), is also one of his most conventional.

“Yeah, well I don’t determine those things. The song determines it. ‘Kiss From A Rose’ was unusual. It reminded me of a song from the sixties or something. I always try to make records that aren’t going to date too quickly, because if you do records that are exactly what’s now, and make the song fit into some sort of… new brutality, it doesn’t work. ‘Kiss From A Rose’ is meant to be normal and lovely. The originality comes in all that stuff he does: [sings] ‘Baby!!!’ in amongst that funny old folk song vibe he’s got going on. And he had all that in his head. I grabbed it as fast as I could.”

One of Horn’s most eyebrow-raising hook-ups in recent years was Belle And Sebastian’s Dear Catastrophe Waitress in 2003: the master of hi-gloss studio sheen meets the icons of ultra-schmindie lo-fi.

“I know, but I loved that song of theirs, ‘Stars Of Track And Field’. My daughter used to play it all the time. And my PA in LA, a girl called Marianne, did their caravan at Coachella, and she set it up. They’d had a bad experience with a producer, and I thought, if they’re gonna be produced, I don’t want anyone to spoil them, you know what I mean? The album after Dear Catastrophe Waitress I didn’t like as much, because I thought the guy tried to make them sound like something, whereas I just tried to get the best version of them.”

And then came a two-headed pseudo-Sapphic pop phenomenon called T.A.T.U.

“I went to see [Interscope chairman] Jimmy Iovine, who’s a real character. He played me the Russian version of ‘Not Gonna Get Us’ by T.A.T.U. and I loved it. He said it was the first time he’d sold a million records in Russia, which probably meant 40 million, because most of them don’t get accounted for. They asked me to write an English lyric, and I sat down with the Russians, which was daunting. So I wrote ‘All The Things She Said’, and I was gonna imply it was more of a teenage infatuation rather than embarking on a lifetime of… whatever.”

Weren’t they really lesbians, then?

“Naaaah! They weren’t really 14, either! They were under 20, which in music business terms means you can get away with it. But they were great girls; a good laugh. As my daughter said, ‘They snogged their way across Europe.’”

There are so many other records we haven’t had time to discuss. I’m kicking myself for not mentioning Marc Almond’s Tenement Symphony album or Propaganda’s ‘Dr Mabuse’ single. As I hand him my copies of the fairy dust-coated ‘Hand Held In Black And White’ and a rare ‘Relax’ white label to sign, I wonder how he’s avoided burning out.

“I have a really good team,” the über-nerd genius says, peering up through those milk bottle specs. “We’re diligent. We don’t go to the pub in the evening. We’d rather work on some vocals.

I don't know a lot, but I know what I like!

- •

- arabchanter

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 12/3/2015

- Posts: 2,393

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

Album 498.

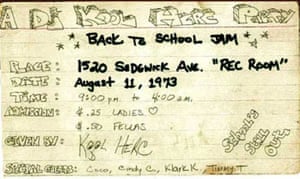

Grandmaster Flash And The Furious Five...................The Message (1982)

The debut LP from the first hip-hop crew to make it to vinyl. The Message is an important milestone in hip-hop's history, displaying the key elements of lyrical delivery with breakbeats garnered from forgotten funk records.

"Scorpio" takes it's title from the Dennis Coffey original, "It's Nasty" from from The Tom Tom Club, while "The Adventures..." is an extended turntable workout by Flash, showcasing the dexterity and creativity that gave birth to the genre in the first place. Swathes of "Rapture" from Blondie, Queen's "Another One Bites The Dust," and "Chic's "Good Times" are weaved together to create a new dancefoor-centred soundscape......the perfect platform for the lyrical talents of the groups MC's.

I don't know a lot, but I know what I like!

- •

- PatReilly

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 25/3/2015

- Posts: 5,580

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

Great album, and a fantastic vocalist in Martin Fry.

I saw him with ABC, touring with Culture Club and Heaven 17 in the 'nineties at the SECC: easily the best act, blew the others off the stage and a great voice still. All the more remarkable then that he had suffered Hodgkin's Lymphona at only 28 in 1985.

Pre Karaoke becoming popular in this country, I used to (try to) sing Poison Arrow in the pub close to closing time in order to impress, but it didn't and I was usually asked to leave. Friday or Saturday nights only.

Thank goodness I've grown up.

- arabchanter

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 12/3/2015

- Posts: 2,393

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

PatReilly wrote:

Pre Karaoke becoming popular in this country, I used to (try to) sing Poison Arrow in the pub close to closing time in order to impress, but it didn't and I was usually asked to leave. Friday or Saturday nights only.

Thank goodness I've grown up.

Don't see that these days,have to admit I loved a wee sing-sang near lousing out time,another thing that's going out of fashion is whistling, I read an article a while back aboot it, and they reckon it's because most people have got headphones/earphones on and have their music rather than making their own by whistling, have to say I'm old school and still whistle and to be honest it makes me happy (don't mock the afflicted), but when was the last time you heard anybody whistling a tune in the street?

Oh, and don't ever grow up, I've heard it's shite!

Got to go out, will catch up the night.

Last edited by arabchanter (06/3/2019 11:24 am)

I don't know a lot, but I know what I like!

- •

- japanarab

- Tekel Towers 1st Team

Offline

Offline

- From: Japan

- Registered: 26/6/2015

- Posts: 978

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

Now you’re talking!!

Last edited by japanarab (07/3/2019 6:54 am)

It's not where you're from it's where you're at.

- arabchanter

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 12/3/2015

- Posts: 2,393

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

Album 499.

Elvis Costello And The Attractions........................Imperial Bedroom (1982)

Six albums in five years and still the driven and prolific Elvis Costello had barely put a foot wrong. He had emerged from punk snarling, dallied with delusions of Abba, homaged soul, even been to Nashville to record an honest-to-goodness country album. What next?! Well he enlisted as producer Geoff Emerick (inspired engineer on The Beatle's Sgt Pepper...) and together they set to work on what would gradually reveal itself to be a darkly seductive collection of lush and heady pop. That is if anything so shot through with melancholy can ever be described as pop.

Deffo be up to date by Saturday night.

I don't know a lot, but I know what I like!

- •

- arabchanter

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 12/3/2015

- Posts: 2,393

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

Album 497.

Prince..............................................1999 (1982)

Right so here we go, let's talk about the " Minneapolis Midget," was he the "ful shillin?' " probably no', was he talented? Hell yeah, was Sheena Easton a "purple people eater?" ........I'd like to think she was, and if Prince fancied dining at the Lady Garden Cafe, would he be going down or more than like having to go up?

Anyways "1999," I fair enjoyed side one, and if you could buy just side one, I'd certainly buy it, but fuck me the other three sides were brutal, in my humbles, sounded like the matinee at the "Tiv" back in the day, a' they clorty fuckers wi' false arms in their raincoats, giving their old man a polish to some shite Scandinavian washing machine repair man having his wicked way wi' some gorgeous housewife who has conveniently forgot to put her knickers on that morning (or so I've been told ![]() .) This reminded me of Michael Jackson with all the squealing and grunting,somebody who really been should have been made to live in "Nonceland" rather than "Neverland," (but we''ll get to that fucker later, I'd imagine)

.) This reminded me of Michael Jackson with all the squealing and grunting,somebody who really been should have been made to live in "Nonceland" rather than "Neverland," (but we''ll get to that fucker later, I'd imagine)

Prince allegedly plays every instrument,wrote every song, and probably had a hand in Italy winning the world cup that year as well, seems like one of those cunts we've all worked who comes oot with "am meh the only fucker graftin' here" So "1999" with tracks ranging from 4 minutes to 9 fuckin' minutes, for me sounded quite the "self-obsessed" album, side one apart I found the rest of the album to be "wanking fodder" at best.

One thing to take away from this boy is, from his humble beginnings as a "test pilot for Airfix" he went on to become quite the pop star, so there is hope for us all yet.

This album wont be going into my collection.

Bits & Bobs;

On his 35th birthday (June 7, 1993), he changed his name to an unpronounceable symbol, a mixture of the male and female signs combined with the alchemy symbol for soapstone. The media began referring to him as "The Artist Formerly Known As Prince," or simply "The Artist." His staff at Paisley Park, on the other hand, called him "the dude." In May 2000, he changed his name back to Prince.

His birth name is Prince Rogers Nelson, taken from his father's stage name - Prince Rogers - in the jazz band The Prince Rogers Trio. His father's real name is John L. Nelson.

Raised in Minneapolis, his nickname in school was "Skipper." Despite his small stature, being only 5'2" tall, he was a very talented basketball player as a teenager and played for one of the best school teams in Minnesota. His brother, Duane Nelson, was also a basketball and football player for Central High School, which they both attended.

He played all of the instruments and wrote all of the songs on his first album, For You (though "Soft and Wet" was co-written by producer Chris Moon). He continued to write, produce arrange and play most instruments on all recordings since.

He wrote hit songs for several other artists including "Manic Monday" for the Bangles and "The Glamarous Life" for Sheila E. Covers of his songs have also been hits, including Chaka Khan's "I Feel For you."

Getting his record deal at 18 and his first album For You coming out at 19, his arrangement with Warner Bros. made him the youngest artist in its history to be given complete artistic control in the studio.

Prince became a Jehovah's Witness in the late '90s, and in accordance with the faith, stopped using profanity in his performances and recordings after his conversion. Prince was known to visit homes randomly in the Minneapolis area to spread the word of the Jehovah's Witnesses. It is believed that he was introduced to the church by bassist Larry Graham of Sly and the Family Stone and Graham Central Station.

Prince was a child prodigy - he learned to play over a dozen instruments before the age of 15. The first song he learned to play on the piano was the original Batman theme when he was 7 years old. In 1989, Tim Burton enlisted him to create the soundtrack for his Batman film, which produced the hit song "Batdance." None of this is coincidental in Prince's mind.

"There are no accidents," he told Details magazine in 1991. "And if there are, it's up to us to look at them as something else."

In July 2007, he gave away copies of the album Planet Earth for free in the UK newspaper Mail on Sunday. It didn't seem like a good marketing move until he announced 21 consecutive London concert dates and sold out all of them.

Prince shunned collaborations. He turned down an offer to duet with Michael Jackson in the '80s, and also refused to perform on "We Are The World." The controversy surrounding Prince's exit from the charity single inspired a Saturday Night Live skit spoofing the event. Billy Crystal played Prince, who led the song "I Am Also The World."

On his 2004 tour, Prince required a doctor backstage to administer a B-12 injection. His rider for that tour also asked for tables at all entry points for collection of gifts and flowers.

In 1980, he was the supporting act on Rick James' tour. Later that year, James headlined for Prince's Dirty Mind tour.

Prince loved ping pong. He and his band played a lot of the table sport when touring. When his Under the Cherry Moon co-star Kristin Scott Thomas was a guest on Late Night with Jimmy Fallon, the host shared a funny story about Prince's love for the game.

Apparently, the singer wanted to play a game of ping pong with Fallon on the show, but he kept changing his mind. His representatives kept calling the host to say Prince wanted to, then didn't want to, then wanted to again, then didn't want to again. It even got to the point where he told Fallon he would play with him off-camera because "he just thinks you'd be fun to play ping pong with." Finally, Fallon said they would have a table set up just in case. Prince did come on the show, but there was no mention of ping pong again.

In 1993, during negotiations regarding the release of Prince's album The Gold Experience, the Purple One realized his contract with Warners meant they owned his master tapes. The Minneapolis star sued for release from the label, and vowed to display the word "Slave" on his cheek until he was free. "If they made jokes I'd say, Go right ahead," Prince told Mojo. "I had their attention."

During an appearance on the Arsenio Hall Show, Prince was asked what household chores he does. He replied: "I can cook, but only one thing - omelets. All my friends have high cholesterol."

Prince was always finicky about giving interviews. When he did allow them, he often confounded journalists by not allowing them to use a tape recorder or even a simple pen and paper to take notes. Sometimes, he didn't even speak at all.

"I used to tease a lot of journalists early on," he told Rolling Stone in 1985, "because I wanted them to concentrate on the music and not so much on me coming from a broken home. I really didn't think that was important. What was important was what came out of my system that particular day. I don't live in the past. I don't play my old records for that reason. I make a statement, then move on to the next."

Prince and his wife Mayte Garcia had a son named Boy Gregory who tragically died of a condition called Pfeiffer syndrome just one week after his birth in 1996. According to Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology, Pfeiffer syndrome is a "rare genetic disorder characterized by the premature fusion of certain bones of the skull (craniosynostosis), which prevents further growth of the skull and affects the shape of the head and face."

The singer's first TV interview was with Oprah in 1996, with the host visiting Paisley Park.

Whilst on a 1987 UK tour, Prince discovered there was no way of getting a baby grand piano up the stairs of London's Chelsea Harbour Hotel for him to practice on, so the workaholic star hired a crane and brought it in through the window.

Prince shared the stage with James Brown when he was 10 years old. "My stepdad put me on stage with him and I danced a bit until the bodyguard took me off," the Purple Maestro told MTV News.

The first song that Prince appeared on was "Stone Lover" by Music, Love and Funk. Recorded in 1976 and released in 1977, the seven-minute plus funk track features him on guitar.

Prince famously repped all things purple in his song titles, album covers and wardrobe. However, according to the singer's sister, Tyka Nelson, it wasn't his favorite hue. "It is strange because people always associate the color purple with Prince," she told Britain's The Evening Standard newspaper, "but his favorite color was actually orange."

Prince was really good at programming a drum machine. He was one of the first to get his hands on the first unit that sampled real drums: the LM-1, of which only about 500 were made. He was able to process the sounds in creative ways, resulting in patterns like the one heard on "When Doves Cry" According to Roger Linn, who created the LM-1, Prince was the most creative user of the device.

ROLLING STONE

December 9, 1982 5:00AM ET

After the critical success of his Dirty Mind LP in 1980 and the subsequent notoriety of last year’s Controversy, Prince, at the tender age of twenty-two, has become the inspiration for a growing renegade school of Sex & Funk & Rock & Roll that includes his fellow Minneapolis hipsters Andre Cymone, the Time and Vanity 6. Yet regardless of the jive that he hath wrought, Prince himself does more than merely get down and talk dirty. Beneath all his kinky propositions resides a tantalizing utopian philosophy of humanism through hedonism that suggests once you’ve broken all the rules, you’ll find some real values. All you’ve got to do is act naturally.

Prince’s quasi-religious faith in this vision of social freedom through sensual anarchy makes even his most preposterous utterances sound earnest. On the title track of 1999, which opens this two-LP set of artfully arranged synthesizer pop, Prince ponders no less than the future of the entire planet, shaking his booty disapprovingly at the threat of nuclear annihilation. Although that one exuberant dance-along raises more big questions than Prince can answer on the other three and a half sides combined, the entire enterprise is charged with his unflagging will to survive — and a feisty determination to eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow, given the daily news, we may die.

Before “1999” whooshes into life, Prince assumes an electronically altered, basso-profundo voice and impersonates the imagined authoritative tone of God himself, creator of libidos as well as souls, prefacing the song’s Judgment Day scenario with this reassurance: “Don’t worry, I won’t hurt you. I only want you to have some fun.” This intro serves Prince well, since 1999 lacks the tight focus of Dirty Mind, his best and most concise LP, which had the feel of emotionally volatile autobiography disguised as vividly descriptive sexual fantasy. Yet the new album doesn’t fall prey to the conceptual confusion that plagued the second side of Controversy, during which Prince raced from politics to passion, funk groove to rock blitz, as if there weren’t room enough for all his inspiration. This time there is, and then some.

Prince develops eleven songs, basically a single album’s worth of material, over the four sides of 1999, with each side comprising two or three extended tracks. Both discs are distinguished by palpably individual moods — the first contains the funkiest, most playful cuts, while the second is made up of slower, more introspective pieces. Two tracks, “D.M.S.R.” and “All the Critics Love U in New York,” qualify as unadulterated filler, and gone are any attempts at the classic three-minute pop song — Dirty Mind‘s “When You Were Mine” was the last word on that, I guess. On 1999, size counts.

Having graduated in record time from postdisco garage rock to high-tech studio wizardry, Prince works like a colorblind technician who’s studied both Devo and Afrika Bambaataa and the Soul Sonic Force, keeping the songs constantly kinetic with an inventive series of shocks and surprises. As “1999” proceeds, for example, he geometrically increases the overdubs until there’s a roomful of Princes partying almost out of bounds, then deftly brings it down to rhythm guitar and percussion while a childlike chorus asks, “Mommy, why does everybody have a bomb?” until — boom! — the groove disappears at its hottest.

Prince’s funniest and slyest effects are reserved for “Let’s Pretend We’re Married,” a string of offhandedly vulgar suggestions transformed with the most basic tools into a quintessential Princeian comic-erotic epic. He first employs minimal but propulsive synth riffs to conjure the atmosphere of a computer-age arcade, pickup bar or, maybe, a space-station lounge. Then he chooses his most angelic falsetto to lure a prospective partner (“My girl’s gone and she don’t care at all/And if she did…”), suddenly switching to his gruffest lower register to complete the couplet: “…So what? C’mon, baby, let’s ball!” Between his ever nastier entreaties, a breezy non sequitur of a chorus (“Ooh we sha sha coo coo yeah/All the hippies sing together”) rushes by like a snatch of transmission from another galaxy, until most everything drops out except a pulsing synthetic bass and Prince himself, desperately aroused, liberally sprinkling his come-ons with the f word. But before his pleas fade into lonely space, he pulls out one last gimmick, a phalanx of cloned voices testifying that he is indeed the Prince of Uptown U.S.A. in a rap wildly mixing the sacred and profane: “Haven’t you heard about me? It’s true/I change the rules and do what I want to do/I’m in love with God, he’s the only way/’Cause you and I know we gotta die someday/You might think I’m crazy, and you’re probably right/But I’m gonna have fun every motherfucking night….”

1999 reaches its climax, however, with Prince’s shortest and sweetest offering, “Free,” which concludes the moody, dub-style third side without any electronic pyrotechnics whatsoever. Prince steps from behind the clanking machinery like a sentimental Wizard of Oz to remind us that “if you take your life for granted, your beating heart will go.” More important, he restates his utopian vision in the most inspirational terms, as if all the battles had been won and he could finally be a lover, not a fighter. “Free” reeks of skewed patriotism, describing the state of the union as much as a state of mind, its march-of-history grandiosity recalling Patti Smith’s “Broken Flag.” Like Smith, Prince is not afraid to be misunderstood — or wrong.

But I think Prince can separate a vision of life from a version of it, as the disturbing postscript “Lady Cab Driver” illustrates. A sequel to Controversy‘s “Annie Christian,” in which Prince tried to duck fate by living “my life in taxicabs,” “Lady Cab Driver” finds him bidding his cabbie to roll up the windows and take him away because “trouble winds are blowin’ hard and/I don’t know if I can last.” But midway through the song, the pain of both personal and public injustice wells up inside him, bursting out in an angry litany of verbal thrusts — “This is for the cab you have to drive for no money at all/This is for why I wasn’t born like my brother, handsome and tall/This is for politicians who are bored and believe in war” — suggesting an ugly backseat orgy of sex or violence. Prince, the lover, not the fighter, then retreats to the demilitarized zone of the bedroom, where he can safely bid us goodbye under the guise of “International Lover.”

A natural goodbye for Prince, but hardly as powerful as the final moments of Dirty Mind, when, during the antidraft “Partyup,” he challenged, “All lies, no truth/Is it fair to kill the youth?” before defiantly commanding, “Party up!” Just as Prince must face the contradiction of creating music that gracefully dissolves racial and stylistic boundaries yet fits comfortably into no one’s playlist, he must also decide whether he can “dance my life away” when everybody has a bomb. All you need is love?

"1999"

Written in 1982 during the height of the Cold War, this party jam has a much deeper meaning, as Prince addresses fears of a nuclear Armageddon. Under the Reagan administration, the United States was stockpiling nuclear weapons and taking a hawkish stance against the Soviet Union, which he referred to as the "Evil Empire."

This scared a lot of people, and Prince voices their concerns:

Everybody's got a bomb

We could all die any day

He's far more optimistic though, responding by making the point that we should enjoy whatever time we have on earth while we still can, even if it all ends by the year 2000:

But before I'll let that happen

I'll dance my life away

In this purple-skied world, life is just a party, and parties weren't meant to last.

Prince doesn't sing on this track until the third line. The first lead vocal is by backup singer Lisa Coleman:

I was dreamin' when I wrote this

Forgive me if it goes astray

Next up is guitarist Dez Dickerson, who sings:

But when I woke up this mornin'

Coulda sworn it was judgment day

Prince takes the next part:

The sky was all purple

There were people running everywhere

All three voices come in on the next line:

Trying to run from the destruction

You know I didn't even care

Originally, Prince envisioned the whole song as a 3-part harmony with Coleman, Dickerson and himself, and they sang it all together. Prince later decided to split up the tracks, letting each voice solo on a line (this is something Stevie Wonder did on "You Are The Sunshine Of My LIfe"). The second verse follows this same pattern, dividing the vocals amongst the three singers.

Prince gave a rare interview in 1999 when he spoke with Larry King on CNN. More surprisingly, he explained the meaning behind this song. Said Prince: "We were sitting around watching a special about 1999, and a lot of people were talking about the year and speculating on what was going to happen. And I just found it real ironic how everyone that was around me whom I thought to be very optimistic people were dreading those days, and I always knew I'd be cool. I never felt like this was going to be a rough time for me. I knew that there were going to be rough times for the Earth because of this system is based in entropy, and it's pretty much headed in a certain direction. So I just wanted to write something that gave hope, and what I find is people listen to it. And no matter where we are in the world, I always get the same type of response from them."

When the new millennium approached, there was a great deal of concern over the "Y2K Bug," since programmers didn't always account for the change to 2000 in their code. There was minimal impact: When the new year hit, we still had dial tones and internet access, and no major networks were compromised. Prince had no fears. "I don't worry about too much anyway," he told King.

Prince was a creative volcano during the time he created this song. After completing a tour for his fourth album, Controversy, in March 1982 he set to work on 1999, but also produced albums for The Time (What Time Is It?), and for the female trio he put together, Vanity 6. Those albums were released in the summer, and in September, "1999" was released as a single. The album followed a month later, and in November, he launched a tour. By the end of the tour in April 1983, the second single, "Little Red Corvette," was climbing the charts and his videos were getting airplay on MTV. With 1999 on its way to selling over four million copies, Prince had crossed the threshold into superstardom.

According to Rolling Stone magazine, when Prince recorded this track, he would go all day and all night without rest, and turn down food since he felt eating would make him sleepy.

Prince grew up in a household that adhered to the Seventh-day Adventist faith, which believes in the Book of Revelations and the apocalypse that will lead to the return of Christ. Prince rejected the religion as "based in fear," and in this song, he puts his own spin on the end-of-the-world prophesy, turning it into a party.

Leading up to his pay-per-view that aired New Year's Eve 1999, Prince said it would be the last time he performed the song. The special a broadcast of a concert held on December 18 at his Paisley Park Studios, with some additional footage from a show by Morris Day & The Time recorded there the night before. "1999" was the last song in the set, which was later released on video as Rave Un2 The Year 2000.

Prince did retire the song, but brought it back in 2007 for his Super Bowl halftime show performance and kept it in many of his subsequent setlists.

A fourth vocalist appears on this song, most notably on the line, "Got a lion in my pocket, and baby he's ready to roar"). That's Jill Jones, who was a backup singer for Teena Marie before teaming up with Prince. She released a self-titled solo album in 1987 on Prince's Paisley Park label. She also appeared in Prince's movies Purple Rain and Graffiti Bridge.

Prince re-recorded this song in 1998 after leaving Warner Bros. Records, who retained rights to the original recording. Prince had serious beef with Warner Brothers when he found out they owned his masters, so he re-recorded this song in an attempt to keep them from profiting from the original version as the titular year approached. The new version reached #40 US at the beginning of 1999.

Many listeners, including Phil Collins, have compared this song to Collins' similar-sounding "Sussudio," released three years later. Collins admitted he was a big Prince fan and often listened to the 1999 album while on tour.

The song only reached #44 in the US when it was first released, but after "Little Red Corvette" took off, the song was re-released, and this time it landed at #12.

Following Prince's death, "1999" re-charted on the Billboard Hot 100 at #27, making it the first song to reach the Top 40 in three different decades ('80s, '90s, '10s) with the same version. "Bohemian Rhapsody" became the second song to reach this milestone when it charted a third time in 2018 following the release of the movie of the same name (its second chart run came in 1992 following its inclusion in Wayne's World).

"Little Red Corvette"

Prince got the idea for this song when he dozed off in backup singer Lisa Coleman's 1964 Mercury Montclair Marauder after an exhausting all-night recording session. The lyrics came to him in bits and pieces during this and other catnaps. Eventually he was able to finish it without sleeping.

Coleman's car was often reported to be a pink Edsel, but she later explained that it was a Marauder (far more sexy than an Edsel) that Prince helped her buy at a 1980 auction.

The song is about sex, but it's just ambiguous enough not to offend most listeners. Many of Prince's earlier songs, like "Head," "Dirty Mind," and "Soft and Wet," were blatantly sexual, which scared off radio stations.

This was Prince's his first Top 10 US hit. It helped propel him to superstar status, a title he lived up to with electrifying live shows and a startlingly prolific output of material, including music, movies and videos.

The album version runs 5:03, but the radio edit was chopped down to 3:08, eliminating the reprise where Prince breaks it down and exclaims, "You must be a limousine!"

The resulting edit (also used in the video), was his most radio-friendly single to this point, with more shiny keyboards and less raw funk than much of his earlier material.

1999 was Prince's fifth album. He had just modest success to this point, his biggest hit being the #11 "I Wanna Be Your Lover" four years earlier.

The title track was issued as the first single in September 1982, about a month before the album was released. That song reached #44 US in December, and "Little Red Corvette" was released as the second single in February 1983. The song made a slow climb up the charts, reaching #6 in May. The next single, "Delirious," didn't come out until August and reached its chart peak of #8 in October.

From November 1982 to April 1983, Prince toured behind the album. As "Little Red Corvette" rode up the charts, he drew far larger crowds - the early dates proved to be some of his last theater shows, as he was a clear arena headliner by the end of the tour.

The line, "She had a pocket full of horses, Trojans, some of them used," refers to Trojan condoms. The "Jockeys" represent men who have previously slept with the girl. These were veiled sexual references that not enough people got to make the song be considered offensive.

Stevie Nicks got the idea for "Stand Back" from this song. She heard it in her car, drove to the recording studio, and put down some tracks. "It just gave me an incredible idea, so I spent many hours that night writing a song about some kind of crazy argument, and it was to become one of the most important of my songs," she remembered in the liner notes for Timespace.

Prince came in and added the keyboard bit. As Nicks tells it, he came up with the riff as soon as he started playing it.

This was one of the first videos by a black artist to get regular airplay on MTV. Michael Jackson was the first to break the color barrier on MTV with "Billie Jean," and "Little Red Corvette" came soon after. The band shot the clip during a tour stop in Jacksonville; the song was already a radio hit when they made it.

In concert, Prince would do some impressive James Brown-style dancing during the instrumental break in this song, complete with an array of spins and splits. These moves are seen in the video, which captures one such performance.

In 2001, Chevrolet put up billboards with a picture of a red 1963 Corvette Sting Ray that said, "They don't write songs about Volvos." In 2003, Chevrolet used this in a commercial that aired for the first time during the Grammys. The ad showed old footage of The Beach Boys performing "My 409" followed by Don McLean singing "American Pie" ("drove my Chevy to the levee"), and then Prince performing this. The camera then goes outside the club to show Chevy's latest model.

There was a Billboard for the Chevrolet Corvette made from this song as well. It had the lyric "Little Red Corvette, baby ur much 2 fast" and Prince's logo over the Corvette. It was displayed behind the National Corvette Museum in Bowling Green, Kentucky in 2003.

After this song became a hit, "1999" was re-released, giving it a second chance. This time, it went to #12 in the US

Last edited by arabchanter (09/3/2019 1:14 am)

I don't know a lot, but I know what I like!

- •

- PatReilly

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 25/3/2015

- Posts: 5,580

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

Big fan of Prince, but I agree four sides can be 'overwhelming'.

But what a talent! Not just as a songwriter, fantastic musician with many instruments, great singer, showman, dancer...... Far far better than Michael Jackson in every way.

- arabchanter

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 12/3/2015

- Posts: 2,393

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

PatReilly wrote:

But what a talent! Not just as a songwriter, fantastic musician with many instruments, great singer, showman, dancer.

This boy's shows similar attributes to which you mention above Pat, but eh widnay buy his album either ![]()

I don't know a lot, but I know what I like!

- •

- arabchanter

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 12/3/2015

- Posts: 2,393

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

PatReilly wrote:

Far far better than Michael Jackson in every way.

But what wis he like at the baby sitting ![]()

I don't know a lot, but I know what I like!

- •

- PatReilly

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Offline

Offline

- Registered: 25/3/2015

- Posts: 5,580

Re: 1001 albums you must hear before you die

arabchanter wrote:

PatReilly wrote:

Far far better than Michael Jackson in every way.

But what wis he like at the baby sitting

Far better than Michael Jackson at that too, I'd imagine ![]()

- arabchanter

- Tekel Towers LEGEND

Offline